Security, Nonces, and Password Hashing

09 Oct 2015One-Time Codes

Today we'll learn about one-time codes, an important concept in website security.

While it's possible to write a regular expression to validate an email address, it's not really worthwhile: even if the user types a correctly-formatted address, that doesn't prove that they've typed an address that exists, or that they own. If I enter "dannb@polandcrodskool.com", for example, or "bill.gates@microsoft.com", I haven't actually entered my email address.

So how do you verify a user's email address? The standard way is to generate some secret, send an email to the address they entered, then have them tell you the secret. In this case, the secret is a one-time code.

A one-time code, also called a nonce, is some randomly-generated piece of data that's discarded after it's used once. A good way to generate a one-time code is with a uuid (universally unique identifier). In JavaScript you can use the node-uuid package:

// after running `npm install node-uuid`...

var uuid = require('node-uuid');

var nonce = uuid.v4();

// => '55cfeb9c-0a64-4300-9ad4-6540d865939a', for example.Having generated the nonce, you can use it to verify the user's email address:

// imagine we're in the midst of creating a new user...

var nonce = uuid.v4();

var mailBody = createVerificationEmail(nonce);

sendMail(user.email, mailBody, function() {

redisClient.set(nonce, user.id, function() {

// report to the user that their account has been created, and

// they should check their email for a verification link

});

});createVerificationEmail is an imaginary function that makes an email body containing some link like http://my.site/verify_email/aa3de659-1340-4848-ae7e-6ec283b97b3a. When the user clicks that link, you can have a handler that verifies their email:

router.get('/verify_email/:nonce', function(request, response) {

redisClient.get(request.params.nonce, function(err,userId) {

redisClient.del(request.params.nonce, function() {

if (userId) {

new User({id: userId}).fetch(function(user) {

user.set('verifiedAt', new Date().toISOString());

// now log the user in, etc.

})

} else {

response.render('index',

{error: "That verification code is invalid!"});

}

});

});

});Exercise: verification email

Either in your microblog or a new project, make a page where new users can enter their email. When they sign up, send them a verification email with a one-time code. Some resources you'll want to use:

- Nodemailer is an npm module for sending email.

- Sendgrid has an API that lets you send small amounts of mail for free.

Password Recovery

Sometimes, users forget their passwords. There are a few ways to help them out in this situation. You can use "security questions," but you shouldn't. You can email them their password, which is problematic for its own reasons. The right way, as you might have guessed, is to use a one-time code. Since you know the user owns the email address they've registered, you can send a nonce to that address to let them change their password.

Exercise: password recovery mails

Implement a page where users who've forgotten their password can request a reset code, and a page where they can redeem it. The redemption page should also require the user to reset their password.

Security

The security of a program is critical, especially when it's connected to the Internet. Not only must you defend your own assets, you have an obligation to your users to safeguard any information they give you. If you store credit card information, you must keep it safe from thieves. Real names and locations may be sought by abusive exes or oppressive governments. Even an email address has value to spammers and phishers.

You must consider security at every step of development. Just as a chain is only as strong as its weakest link, a single flaw in your code's security logic can be all it takes to to create a successful exploit, no matter how correct the rest is. Even minor flaws, abused together, can lead to a major exploit. The fundamental principle in security is defense in depth: confirm at every stage that what's going on makes sense in context, like a bureaucrat who demands every form filled out in triplicate, signed, witnessed, and sealed.

Of course, like a demanding bureaucrat, carefully-secured code can be frustrating to work with. Faced with a frustrating interface, users may look for ways to work around it, compromising security for the sake of expedience. A classic example is password-complexity rules: the IT department demands that every password contain lowercase and uppercase letters, numbers, and nonalphanumeric characters, and that they be rotated every 30 days. Unable to remember these cryptic passwords, users write them on a sticky note and put it on their monitor, where any burglar or pizza guy can see them.

Balancing the need for careful security with users' impatience and carelessness is a difficult art form. It gets even harder when you add social engineering to the mix. There aren't any hard-and-fast rules, but in general, keep in mind that people will usually do whatever's easiest. Try to make sure the easiest thing is also the secure thing.

There are far too many aspects of security to cover in one day (or one month). Today we'll go over code injection, one of the most common security flaws, and password hashing, one of the most important ways to protect your users.

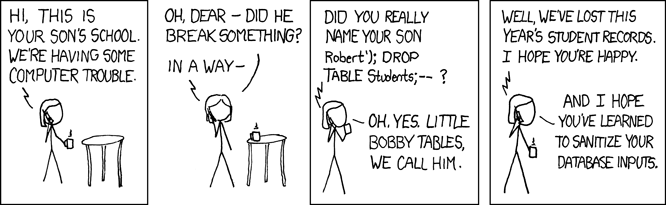

SQL Injection

The single most common security flaw in web applications is SQL Injection. Consider this code:

router.post('/login', function(request, response) {

database.query("select * from users where username = '"

+ request.body.username + "'", function(error, result) {

// check password and log the user in

});

});

This code has a SQL injection vulnerability. If someone types '; drop table users; --' into the username field, the full query sent to the database will be:

select * from users where username = ''; drop table users; --'

The JavaScript code meant to send the user-input to the database as a value to be inspected. However, careless programming allowed an attacker to send their own SQL code, so in this example the users table gets dropped (Remember that -- is the comment character in SQL, so the trailing ' won't cause an error).

The solution is easily said, although it requires some attention: Never use string concatenation with user input to build a SQL query. Ideally, you should use a query builder like Knex. If you must use raw SQL strings, keep user input in the parameters list:

router.post('/login', function(request, response) {

database.query("select * from users where username = $1",

[request.body.username], function(error, result) {

// check password and log the user in

});

});

XSS (Cross-site Scripting)

XSS could also be called "Javascript injection." Just as SQL injection occurs when data that should've been a plain value gets used as SQL code, XSS occurs when data that should've been a plain value gets used as HTML or JavaScript code. Consider this code from an imaginary chat application:

socket.on('message', function(message) {

var div = document.createElement('div');

div.innerHTML(message.body);

document.getElementById('chat-pane').appendChild(div);

});

What if message.body contains <script>alert('hello')</script>? The script tags will be evaluated as HTML, and the alert will run in the user's browser. XSS exploits allow attackers a range of options, from annoying alerts to stealing session tokens. Always use element.innerText or $(element).text to add user input to an element:

socket.on('message', function(message) {

var div = document.createElement('div');

div.innerText(message.body);

document.getElementById('chat-pane').appendChild(div);

});

Templating systems like Jade are also a vector for XSS vulnerabilities. Consider this profile page:

.profile-section

!= user.bio

If a malicious user puts <script> tags in their bio, they'll be served to the browser as HTML, and users who visit the malicious user's page will run that JS in their own session. Use the = operator to html-escape any user input:

.profile-section

= user.bio

Password Hashing

Password hashing is an important way to protect your users. You should never store users' passwords in plaintext; instead you should use a cryptographically-secure hashing algorithm. A hashing algorithm takes some input, like a password, and applies mathematical transformations to it that ensure the original input can't be discovered by inspecting the output. Here is a simple hash algorithm:

function simpleHash(input) {

var hash = 0;

for (var i = 0; i < input.length; i++) {

hash = hash ^ input.charCodeAt(i);

}

return hash;

}

This hashing algorithm isn't very good, as it has a lot of collisions: inputs that hash to the same output. New and improved hashing algorithms are introduced every so often; the current winner is SHA-256. But for demo purposes, you can use an older system, MD-5 which is available right in your terminal:

md5 -s password

#MD5 ("password") = 5f4dcc3b5aa765d61d8327deb882cf99

If we try it with string only one character away, or with two characters transposed, we get a completely different result:

md5 -s pastword

#MD5 ("pastword") = 6a15a9a75145971d8317560bb79bed6e

md5 -s passwrod

#MD5 ("passwrod") = 919e682cac825d430a580e842ff0bbc4

Although MD-5 has flaws, it demonstrates the defining features of hashing: a given input always generates the same output hash, but the process is irreversible --- knowing the hash tells you nothing about the input.

Password salting

Actually, hashing passwords isn't enough. An attacker who gets access to your hashed passwords can create a rainbow table, a list of thousands or hundreds of thousands of common passwords and their hashes, and use it to look up a hash and determine its corresponding plaintext. To combat this, you should add a salt to your passwords: a chunk of random text that's added to the password before hashing. The salt isn't secret, but it should be different for each user. This forces attackers to rebuild the rainbow table for each user--a computationally infeasible task.

Demo: the pwd module

The NPM module pwd makes it easy to implement both hashing and salting. Here is a simple demo, in which only one user record is stored in a "database" but that record includes the user's unique salt and password hash, which can be used subsequently for authentication.

var pwd = require('pwd');

// The user's registration info:

var raw = {name:'user', password:'password'};

// What gets stored (salt and hash TBD):

var stored = {name:'user', salt:'', hash:''};

function register(raw) {

// Create and store encrypted user record:

pwd.hash(raw.password, function(err,salt,hash) {

stored = {name:raw.name, salt:salt, hash:hash};

console.log(stored); //==>

// { name: 'user',

// salt: 'BcRp8aw2jxNO...',

// hash: '3Myz3F5mz3Hj...' }

})

}

function authenticate(attempt) {

pwd.hash(attempt.password, stored.salt, function(err,hash) {

if (hash===stored.hash)

console.log('Success!')

})

}

register(raw);

// After delay, try authenticating:

setTimeout(function() {authenticate(raw)}, 500);

Exercise: password salting and hashing

Take one of your previous projects that allowed signing in (or use the login sample code, if you prefer). Update it so that when a user signs up or changes their password, the password is salted and hashed using pwd. When a user signs in, hash the supplied password and compare it to the stored hash.