Regular Expressions & Recursion

06 Oct 2015Today, we'll be looking at a couple of tools that will be useful to you throughout your coding career: Regular expressions and recursion! (This episode brought to you by the letter "R").

Regular Expressions basics

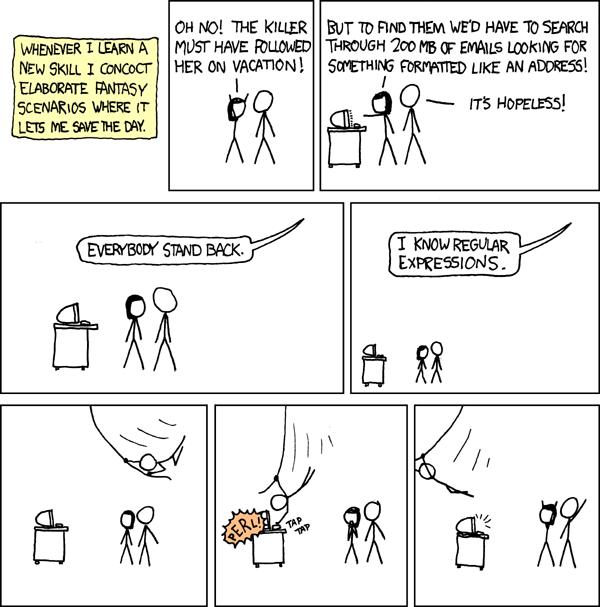

RegEx are one of the most useful tools to master, not just for programmers, but for anyone who works on computers and needs to occasionally look for data. As usual, there's a relevant XKCD:

They're basically a pattern-matching tool, and are not specific to JavaScript or any other programming language (though they are associated strongly with Perl). With them, you can create complex searches that let you quickly sift through massive piles of information. We'll start out by looking at them in the context of JavaScript, but remember that you can use them in a surprising number of places--not just other languages, but at the terminal, in your text editor of choice, and even in some word processors.

RegEx in JavaScript

Regular expressions in JavaScript are a new kind of object--there is a constructor for them, so you can create them with new RegExp(), but there is also a literal syntax that is more commonly used:

var pattern = /cat/;

This regular expression will match any occurrence of the string 'cat'. You can use regex to search through strings by using string methods. Given the following string:

var string = "Consecutive cats concatenate caterwauling compulsively."

... we can use several different methods.

Regex with String methods

The simplest string method to work with is probably search, which will go through the string looking for anything that matches the supplied regular expression. With our above pattern and string, we would use it like so:

string.search(pattern);

Doing that will return the character index of the first match in the supplied string--in this case, 12. If we want more information, we can use the match method instead; string.match(pattern); will return:

[ 'cat', index: 12, input: 'Consecutive cats concatenate caterwauling compulsively.' ]

This is telling us that the thing that matched /cat/ was 'cat' (which seems a little silly, at this point), it occurred starting at character index 12, and the whole input string was 'Consecutive cats concatenate caterwauling compulsively.'.

Finding matches is all well and good, but what about changing content with regular expressions? We can do that with replace:

string.replace(pattern, 'Shackleton');

// --> Consecutive Shackletons concatenate caterwauling compulsively.

Note that in none of these cases are we dealing with any more than the first occurrence of 'cat'. The final string method that uses regex will change that trend:

string.split(pattern);

// --> [ 'Consecutive ', 's con', 'enate ', 'erwauling compulsively.' ]

Here, we've used the split method that we have seen before to chop apart the string into an array, with array items delimited by /cat/.

RegEx methods

In addition to the string methods we can use regex with, RegExp objects themselves have two methods available to us: exec and test. They both take a string as an argument. exec is essentially a flip-flopped version of match, returning a bunch of information about the match found. test will return a single Boolean value indicating whether the match is in the string or not:

pattern.exec(string)

// --> [ 'cat', index: 12, input: 'Consecutive cats concatenate caterwauling compulsively.' ]

pattern.test(string)

// --> true

And that's it for regex methods! From here on out, everything we'll be dealing with will be the structure of the regular expressions themselves.

RegEx syntax

Now comes the part that many find intimidating about regex: the syntax. The regular expression that we saw above was quite simple, but we can use the regex special characters to search for more general patterns than our very specific /cat/. Special characters are often preceded by \, which is the escape character. When special characters don't require a preceding \, including one will make the character into a literal rather than a special character. For example, * is a special character than means "any number of times", but \* means literally the character "*".

Special characters

The special characters (which generally stand in for sets of other characters) are:

- . Any character other than a line end

- \w Any word character (letters or digits)

- \W Any non-word character (neither letter nor digit)

- \d Any digit character (0-9)

- \D Any non-digit character (anything not 0-9)

- \s Any space character (tabs, spaces, etc)

- \S Any non-space character

- ^ The start of a line or string

- $ The end of a line or string

- \b A word boundary; the space between a \w and a \W

- \B Any character that isn't a word boundary

- \t A tab character

- \n A newline character

- \r A carriage return character

To try these out, we can use our earlier string with some different regexes:

string.match(/c.t/g);

// --> [ 'cut', 'cat', 'cat', 'cat' ]

Because we've used the g flag here, match will return an array of all the possible matches for "c" plus any single character plus "t". Look over the following regex patterns and see if you can predict what they'll come up with:

/e\Wc/g/\D\W$//\S\sc\w\D/g/\b\w\S\D\w\s/g

Repetitions

So we've seen so far that we can make our searches pretty confusing and hard to parse by stringing together all kinds of wildcard characters. We have options to make things (arguably) easier to read, though, in the form of repetition characters:

- * Zero or more repetitions of the preceding character

- + One or more repetitions of the preceding character

- ? Zero or one repetitions of the preceding character

- {x, y} x to y (inclusive) repetitions of the preceding character

- {x, } x or more repetitions of the preceding character

- {x} Exactly x repetitions of the preceding character

With these, we can start to build even more intersting expressions:

string.match(/c\w{1,5}\b/g);

// --> ["cutive", "cats"]

string.match(/c\w{6,}\b/g);

// --> ["concatenate", "caterwauling", "compulsively"]

string.match(/ca\S\d*/g);

// --> ["cat", "cat", "cat"]

Greedy vs. non-greedy expressions

So what will happen with the following regex?

string.match(/c.*c/g);

It seems like it should return an array of all the letters that go from 'c' to (shining) 'c', but that isn't the case. That's because regular expressions are by default greedy--they will grab the largest possible match for their expression, so the above regex will return ["cutive cats concatenate caterwauling c"]. In order to make regex non-greedy, we have to append a ? to our repetition character; to get the result we first thought we'd get, we need to do it like this:

string.match(/c.*?c/g);

Ranges and groups

We've already seen some character groupings, like \w and \d, but what if we want to only find digits from zero to five, or uppercase letters? We can make our own ranges in regex fairly easily by enclosing ranges in square brackets, like so:

string.match(/[a-m]/g);

We can also negate our ranges with the ^ character; [^0-9] means "any single character not zero through nine," which is the same as \D.

The \w special character is essentially shorthand for [a-zA-z0-9]. We can add more things to that pattern if we want an extended set beyond \w--for example, if we want to ensure that an entered password only contains letters, numbers, and a few special characters, we can do something like:

function goodCharacters(input) {

return !/[^a-zA-Z0-9_$|%&]/.test(input)

}

If there are multiple sequences of characters we're interested in checking for, we can enclose the acceptable patterns in parentheses, separated by pipes:

string.match(/(co|ca)(n|t)/g);

// --> ["cat", "con", "cat", "cat"]

Grouping and backreferences

One of the most powerful things that you can do with regular expressions is save bits of your search to refer to later--potentially later in the same expression. You can do this by enclosing the term or terms that you're interested in in parentheses to capture the result, and then using \ followed by a number representing the match number--\1 for the first match, \2 for the second, and so on. We could use this to check for five-letter palindromes like so:

function fivePal(word) {

return /(\w)(\w)\w\2\1/.test(word);

}

Grouping like this becomes even more powerful when you bring in the replace method; you can use the captured groups in the replacement text by using dollar signs--for example $1 for the first thing that was captured. given a list of names, you can swap from <first> <last> order to <last>, <first> like so:

var name = 'Tom McCluskey'

name.replace(/(\w+)\s(\w+)/,'$2, $1');

Flags

We've already seen one of the flags: g, which makes our searches global rather than just grabbing the first result. There are only a total of three in JavaScript:

- g Make searches global

- i Make searches case-insensitive

- m Make searches multi-line

A Word of Warning!

Now that you've learned your way around most of what regex have to offer, it's pretty tempting to use them everywhere. There are some limitations to what they can do, however. In particular, regex are not well-suited to parsing HTML, because HTML is not a 'regular' language; it has patterns that cannot be encompassed by regular expressions. For example, take the follwowing:

var single = '<p>This is a <span>single</span> span paragraph</p>';

var double = '<p>This is <span>a <span>single</span> span</span> paragraph</p>';

var triple = '<p>This <span>is <span>a <span>single</span> span</span> paragraph</span></p>';

And try to write a regular expression that will correctly match all the <span>s in all the variables. Feel free to refer to this classic StackOverflow answer for inspiration.

Regex problems!

- As many of you have observed, regular expressions show up frequently in very clever solutions to some Code Wars problems. You can search through problems by tags, so hunt down some regular expression problems that sound interesting and see what you can do with them.

- RegExCrossword is a pretty neat site that affords plenty of chances to practice with regular expressions.

- RegExGolf is pretty challenging, but a lot of fun.

Recursion

As you might guess from the above, recursive functions are those functions which call themselves in their own bodies. Recursion in programming can be an amazing tool, but it can also result in dense, hard-to-understand code. There are some problems, though, that are so much simpler with recursion that it is the most sensible way to approach them.

So when does it make sense to use recursion? You can theoretically use recursion pretty much any time you're using a loop, but where it really makes sense is where you need to do something repetitively with only minor repetition until a certain condition is reached. The classic example of recursion is to implement the mathematical factorial operator, which is generally written !. Factorial is the product of a number and all the numbers less than it, down to 1. So 6 factorial is 6*5*4*3*2*1, or 720. We can write a function to find the answer in JavaScript like so:

function factorial(number) {

for(var i = number-1; i > 1; --i) {

number *= i;

}

return number;

}

This works just fine with a loop, but we can also do it recursively:

function factorial(number) {

if (number === 1)

return 1;

return number * factorial(number-1);

}

This is actually a very intuitive way to think about the problem--once you get used to it, at any rate. You're setting an edge case: the factorial of 1 is 1. Other than that, the factorial of any number is equal to that number times the factorial of one less than that number:

factorial(4) === 4 * factorial(3)

factorial(4) === 4 * ( 3 * factorial(2))

factorial(4) === 4 * ( 3 * ( 2 * factorial(1)))

factorial(4) === 4 * ( 3 * ( 2 * (1)))

factorial(4) === 24

Edge cases are ubiquitous in recursion--they're how you tell the function when to stop. When you have a problem that feels like it should have a recursive solution but you're not quite sure how to approach it, one of the best places to start is defining the edge condition. With factorial, it's fairly straightforward--we know we don't want to keep taking factorials forever, so we have to stop somewhere, and 1 is a logical conclusion--for multiplication, 1 is an idempotent value: it doesn't change the input value. One times anything is that same thing. For addition, zero is idempotent, since zero plus anything is that thing.

Warning!

When you are playing around with recursion, you will see RangeError: Maximum call stack size exceeded at some point. This is JavaScript telling you that you have neglected to enter an edge condition, or that there is a problem with your code such that it is making something that doesn't meet the edge condition, and that because of this you have created an infinite loop. That's perfectly normal, and nothing to be worried about--but I find that if you're doing recursion in the browser and get an infinte loop, you can sometimes lock up the browser; I'd advise testing your recursive code in Node rather than the browser.

Some problems

Powers: Finding powers of numbers is pretty simple with Math.pow, but imagine for a moment that we didn't have that tool available to us. If we were to write our own function to find the value of a number raised to a particular power, we could do that recursively. Consider powers of 2:

2^1 === 2

2^2 === 2 * 2

2^3 === 2 * ( 2 ^ 2)

Try writing a function that recursively finds the value of a number raised to a particular power.

Max of an Array: Say we had an array of numbers, and we wanted to be able to find the maximum number in that array. The imperative way of doing that would probably be to loop through everything in the array, checking the value of each thing, and then setting a variable equal to the highest value we've found so far, then returning that value at the end of the loop, like this:

function maximum(array) {

var maxSoFar = 0;

for (var i = 0; i < array.length; i++) {

if (array[i] > maxSoFar) {

maxSoFar = array[i];

}

}

return maxSoFar;

}

We can also solve this problem recursively, though. How do we do that? Well, we can start with our edge cases. The maximum of an array with a single value in it is that single value, of course, so there's an edge case. And the maximum of an array with two values in it is equal to whichever is bigger. What about after that? Well, the max of an array with three values in it is equal to the either the first thing, or the maximum of the other two things. In other words:

max([x]) === x

max([x,y]) === x > y ? x : y

max([x,y,z]) === max([x, (max([y,z])])

See if you can bulid a function that recursively finds the maximum value of an array of numbers, based on the above.

Recursing through objects: Recursion doesn't all have to be about numbers, though! Deeply nested objects in JavaScript are an ideal place to use recursion. Say you wanted to be able to list all the descendants of a particular object, for example. It's hard to tell exactly how deep any given object can go. The beauty of recursion, though is that you don't need to know how deep the stack goes--instead of having to loop through everything yourself, you can just tell each object to report its children and all of their descendents. Those objects will in turn pass that order farther down the chain, until the chain finally reaches its end. At that point, the last object will say "it's just me here" to its parent, which will then report on up, and so on until the top is reached.

Write a function that will find all the children of a given object. One important note: because objects can contain circular references, you might want to find a way of marking the objects that you've already looked at, in order to prevent infinite loops. Can you use this method to make a deep copy of an object?

The Towers of Hanoi: This is a fun one! The idea is that you have three pegs. On one peg, there are a certain number of discs, each smaller than the one below it. The puzzle is to move the stack from one peg to another, while only moving one stack at a time and never putting a larger disc on top of a smaller. You can try it out online here if you'd like. This is solvable for any number of discs. Write a function that will return an array of arrays that describes the sequence of moves to get the whole stack from the start to the finish. For example, given a stack of three rings and poles named 'start', 'goal', and 'temp', the function should behave like this:

hanoi(3, 'start', 'goal', 'temp');

// --> [ [ 'start', 'goal' ], [ 'start', 'temp' ], [ 'goal', 'temp' ], [ 'start', 'goal' ], [ 'temp', 'start' ], [ 'temp', 'goal' ], [ 'start', 'goal' ] ]

More: There are a ton of great problems on Code Wars for further playing around with recursion. Check them out!